Visual Guide to Painful Hymenopteran Stings

For most of us, insect stings are a thing to avoid. That’s not the case for entomologist Justin O. Schmidt. That’s because Dr. Schmidt has dedicated his life to studying venomous hymenopterans, the order of insects made up of ants, bees, and wasps. Through his research, he has been stung countless times. As a result, he developed the Schmidt Sting Pain Index.

I stumbled upon Schmidt’s work after seeing this video of warrior wasps. One of the noteworthy characteristics of warrior wasps is that when threatened, they rhythmically flap their wings against their bodies in perfect synchrony, producing a sound not unlike marching soldiers. The other characteristic these wasps are known for is a sting that hurts!

Just how much does a sting from a warrior wasp hurt? According to the pain index developed by Schmidt, the warrior wasp tops in at a 4 - the highest level of pain in the scale. What’s more, the excruciating pain will last at least 60 minutes before subsiding even the slightest.

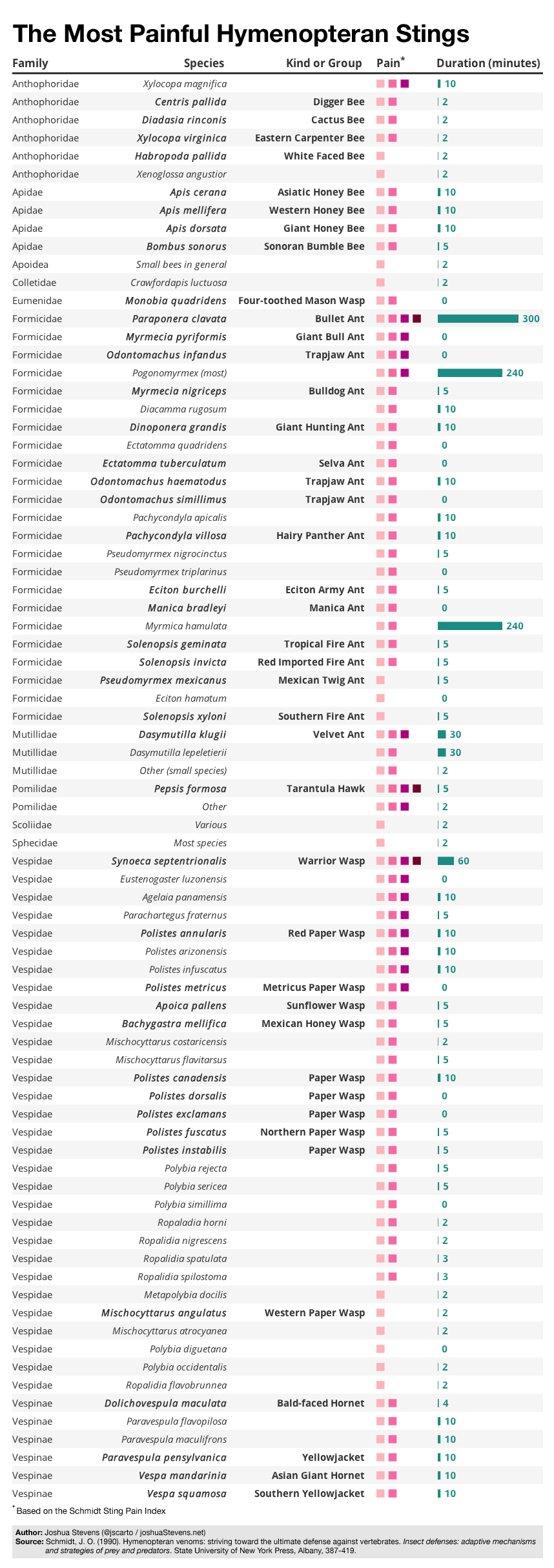

The warrior wasp is not the most painful sting recorded in Schmidt’s index, however. In fact, it pales in comparison to some other insect stings. To date, Schmidt has cataloged the painful stings of nearly 80 different hymenopteran species, from various ants to the giant Asian hornet.

So which venomous insect is really the king of sting? I’ve turned Schmidt’s data into this visualization to help you decide.

In addition to the data provided by Schmidt, I’ve added the common name of the insect, or the group to which it belongs, where possible. Due to Schmidt’s expertise and rigor, many of the species listed are not commonly known. For these, I was unable to track down any common identifier.

Pain is subjective. It’s possible that one person might prefer a short-lived category 4 sting over a longer, weaker category 1 or 2 sting. According to these data however, the bullet ant (Paraponera clavata) is the clear winner. The immediate category 4 pain from a bullet ant lasts for 5 hours! It then takes 24 hours to subside, with residual pain reported up to two weeks later. No wonder it is considered the most painful sting not just among hymenopterans, but all other insects!

Such a powerful sting has earned the bullet ant a place among the Satere-Mawe, a tribe in the Brazilian Amazon rain forest. During their coming-of-age initiation, young members of the Satere-Mawe wear mittens lined with bullet ants. For 10 minutes initiates dance in the stinging mittens to prove their courage. They must do this not once, but 20 times before completing their ceremonial journey.

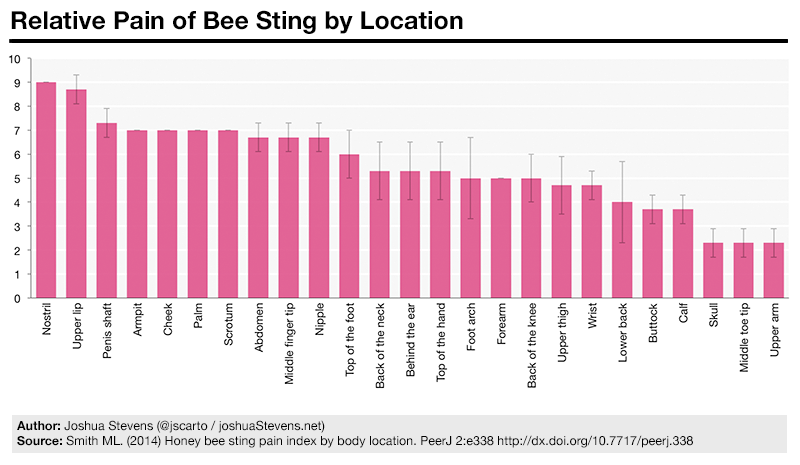

Pain and Place: The Bodily Geography of Schmidt’s Index

In addition to the subjective nature of pain, location matters when it comes to insect stings [3]. Using honey bees as a baseline, Michael L. Smith tested the variance of Schmidt’s Pain Index based on where the sting occurred. According to Smith’s research, the nostril was the worst place to be stung, followed by the upper lip.

The timing of the sting and number of subsequent stings were not significant factors in pain level. Smith hypothesizes the important role of location is due to naturally protected areas that are rarely stimulated (e.g. nostrils) and soft areas that enable greater penetration. Even in its most sensitive locations, Smith notes that the human body has defenses:

Stings to the nostril were especially violent, immediately inducing sneezing, tears and a copious flow of mucus. The sting did autotomize in the nostril (self-severed when the bee was pulled away). The copious mucus flow, however, may help prevent subsequent stings to the area during a natural attack. (p. 6)

Stings That Kill

In the United States, bee and wasp stings are responsible for the deaths of about 40 people each year. This makes bees more deadly than dogs, spiders, and snakes [2]. Even sharks, which are one of the most feared animals in the world, have only killed 3 people in the US during the years 2006 - 2010.

Nearly all of the deaths related to bee stings are the result of anaphylaxis, which is a severe allergic reaction that can lead to difficulty in breathing, dizziness, unconsciousness, and ultimately death. Anaphylaxis is the result of compounds in the insects’ venom that are not related to the amount of pain inflicted. As a result, the Schmidt Pain Index is not an indicator of how deadly an animal is to humans. Small bees (pain level 1-2) kill far more people than the bullet ant (level 4).

The deadliness of smaller, less painful insects has more to do with their behavior and the likelihood of an encounter. Africanized honey bees - the famed “killer bees” - are particularly deadly because of their aggressive swarming characteristics. They are easier to provoke, attack in large numbers, and are known to chase their targets for long distances. Just last year, a man in Texas was killed after a swarm of nearly 40,000 killer bees descended upon him.

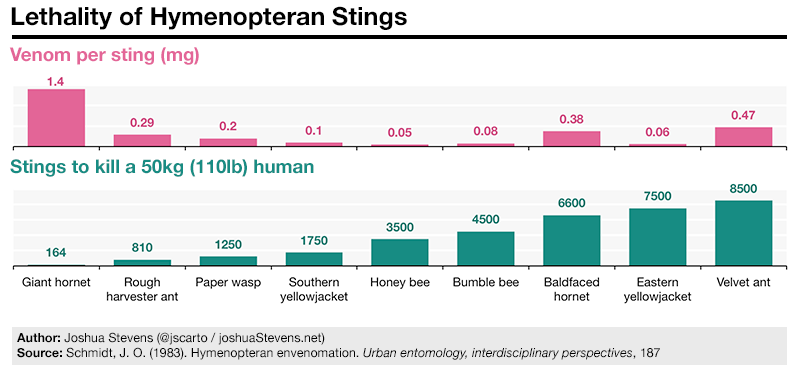

A Different Dose

Just as location affects pain, the biochemistry of the species’ venom influences its lethality. Each species has a slightly different arrangement of enzymes in their venom, making some more lethal than others. In addition, each species injects a different amount of their venom, per sting. For example, the Honey bee injects 0.05mg of venom per sting while the fire ant can inject up to 0.1mg [3]. Typically, insects sting other insects or smaller animals that attempt to prey on them, so their venom has not evolved for the purpose of killing humans. But with a high enough dose - delivered by the right number of stings, hymenopteran venom can be lethal. Just how much does it take?

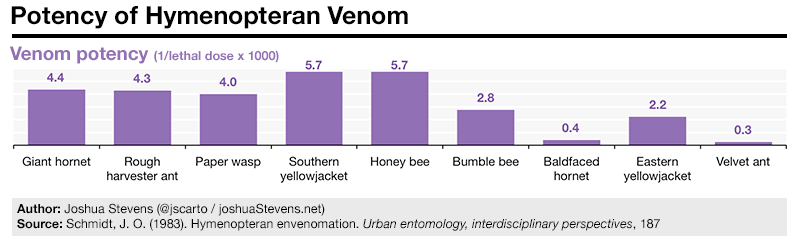

These data show the amount of venom required for death to occur as a result of the venom alone. Secondary effects, such as anaphylaxis, are not included.

Don’t be tricked by the Giant hornet’s heavy-handed dose, however. Even though it can kill with the fewest stings, the fact that it delivers far more venom than the others means that, relatively speaking, its venom is not the most potent. To be lethal to a 50kg human, the Giant hornet must inject a total of 229.6 mg of venom. In contrast, a honey bee needs to inject only 175 mg of its venom. The graph below shows how these venoms stack up in terms of potency.

With its high potency venom and greater likelihood to be encountered, its easy to see why the honey bee kills far more people than the giant hornet or any other hymenopteran!

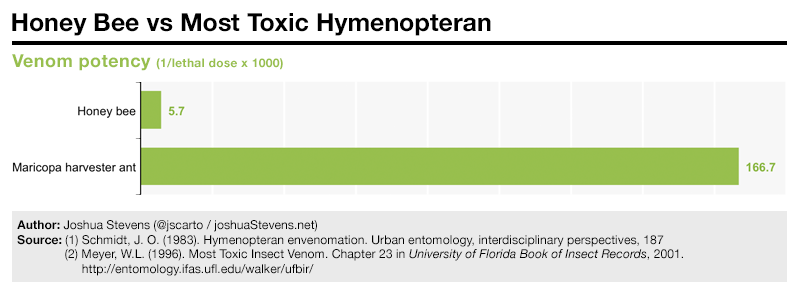

Although it is responsible for the most deaths and has more potent venom than some similar species, even the honey bee has weak venom compared to the most potent of all hymenopterans. That honor goes to the Maricopa harvester ant. This species of ant has a venom that is nearly 30x more potent than the honey bee, making its venom the most potent of all insects.

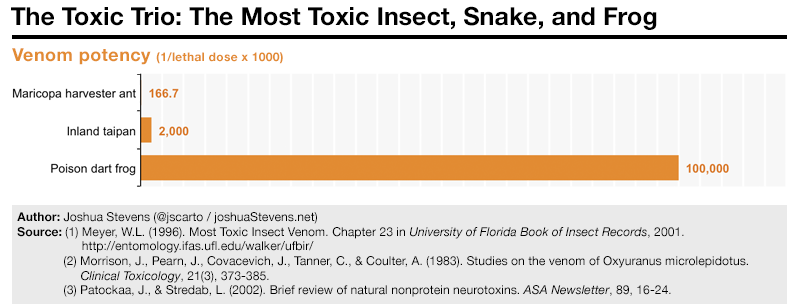

It’s one thing to have the most potent insect venom. Having the most potent venom in the animal kingdom is another. How does the Maricopa harvester ant compare to the world’s most toxic snake and the poison dart frog? I wondered that too. As it turns out, it’s not even close.

The poison dart frog is more potent than any snake, spider, or ant venom. It even leaves the infamous Irukandji box jellyfish and venomous cone snails (not pictured) in the dust.

It’s important to note the difference between poison and venom. Both are toxins that are produced to either protect the animal in defensive situations, or to help capture prey. The key difference is that venom is injectected while poison is injested. In other words, if it bites you and you die: it’s venomous. If you bite it and you die: it’s poisonous.

Fortunately for us the poison dart frog fits in the latter category.

Closing Thoughts

Aside from their interestingness, these data shattered a few of my preconceptions about insect stings. Being in the outdoors often has given me my fair share of stings and encounters with various bees, wasps, and hornets. Among all of these, I avoided hornets the most (the bald-faced hornet is common in every area I’ve lived). I’m willing to bet that many others also view hornets as nastier, more painful stingers than other wasps and bees.

But according to the data, that needn’t be so. These hornets are no more painful than the common yellowjackets and bumble bees that frequent backyards and gardens. In fact, the pain subsides more quickly and their venom is much weaker.

So what gives? Why would we fear the insects we see less frequently (such as hornets) while remaining comfortable around those most common to us (like honey bees) - despite the latter being more painful stingers and even more deadly? Personally, I think the question reveals the answer. As in many situations, it seems that fear of the unknown outweighs reality.

While I won’t be hunting for a pet hornet anytime soon, I’m glad I took a look at these data and hope some of the findings were as eye-opening to you as they were for me.

References

[1] Schmidt, J. O. (1990). Hymenopteran venoms: striving toward the ultimate defense against vertebrates. Insect defenses: adaptive mechanisms and strategies of prey and predators. State University of New York Press, Albany, 387-419.

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Compressed Mortality File 1999-2010 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released January 2013. Data are compiled from Compressed Mortality File 1999-2010 Series 20 No. 2P, 2013. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/cmf-icd10.html on Jun 28, 2014 1:00:26 PM

[3] Freeman, T. M. (2004). Hypersensitivity to hymenoptera stings. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(19), 1978-1984.

[4] Smith ML. (2014) Honey bee sting pain index by body location. PeerJ 2:e338 http://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.338

[5] Schmidt, J. O. (1983). Hymenopteran envenomation. Urban entomology, interdisciplinary perspectives, 187.